Supporting the delivery of essential services during COVID 19 restrictions

Written by Sophi MacMillanThe PVC industry in Australia is crucial to the delivery of several essential services in the Australian economy.

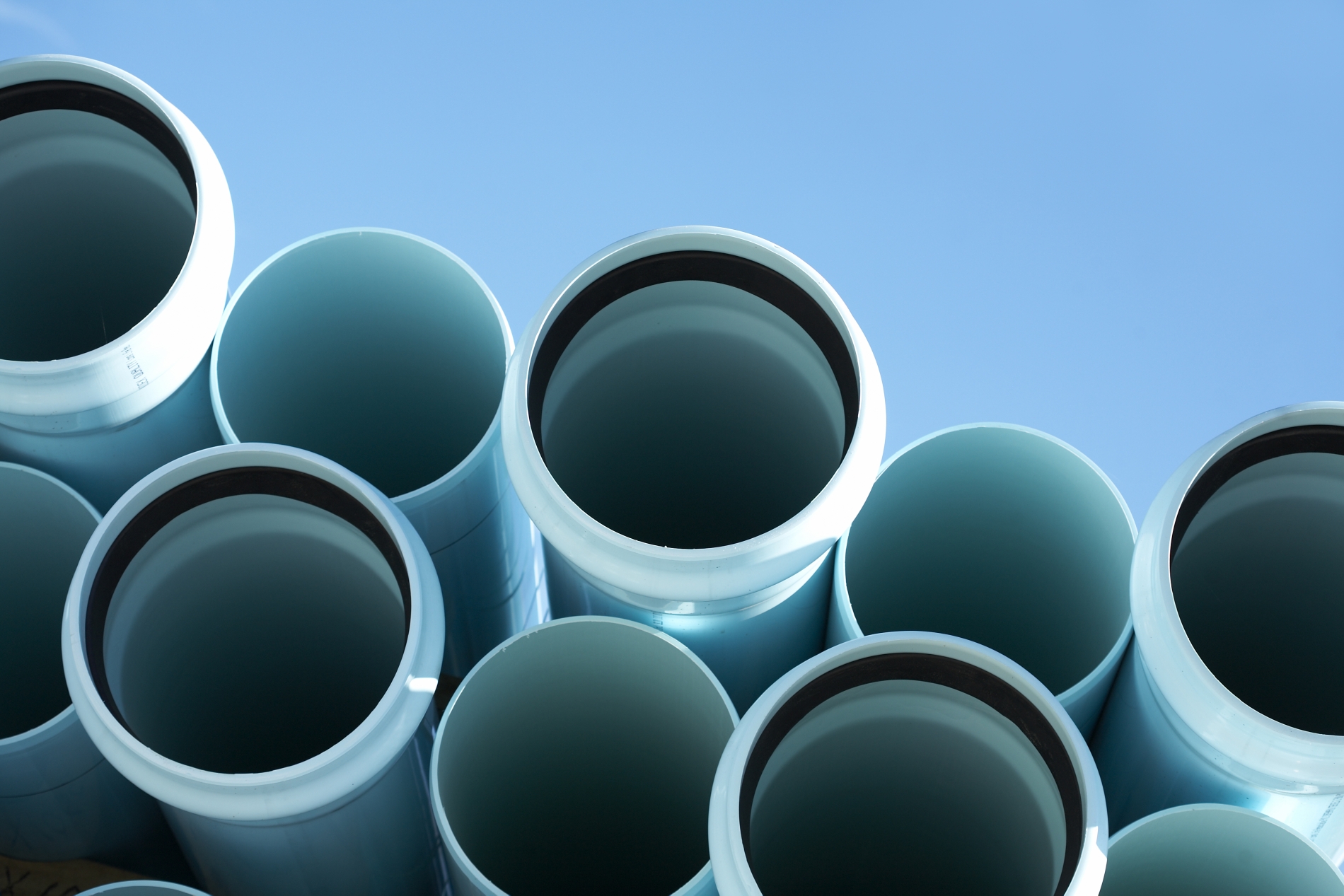

Approximately three quarters of the local PVC industry is engaged in the manufacture and distribution of products for essential utility services including potable water, stormwater management and sewer services, energy and telecommunications delivery, plastics recycling and key construction products for major projects such as healthcare facilities.

Others in the sector produce essential processing chemicals and compounds, specialist food packaging and vital medical products, manufactured here in Australia.

The local industry directly employs over 2,500 people and contributes well over $3 billion to the national economy. PVC products contribute to virtually every sector of the economy and it is vital that the industry remains operational through this Covid19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, the safety and well-being of the industry's employees and customers is paramount. Members of the Vinyl Council of Australia are implementing appropriate measures to protect their workers, contractors and customers from risk of exposure at their work places, and will continue to ensure the safety of their operations.

Recyclable PVC plays an important technical role in packaging

Written by Sophi MacMillanVersatile and recyclable, PVC (vinyl) provides significant benefits as a specialist packaging material; yet recovering this material for sustainable reuse presents challenges. Sophi MacMillan, Chief Executive of the Vinyl Council of Australia offers some practical solutions.

For more than half a century, PVC or vinyl has been used on a global basis to meet specific functional food and beverage packaging needs. It suits many different food types, offering excellent clarity, unsurpassed physical properties, including heat tolerance, controllable gas and moisture vapour transmission capabilities and exceptional sealing performance.

Most vinyl is used in long life products, particularly building products from pipes, cabling and flooring to window frames and wall profiles, all of which are recyclable. Vinyl used in packaging – such as bottles, thermoformed punnets, pharma blister packs and cling films - represents about 6% of the material’s usage in Australia.

In these applications, vinyl plays an important role in protecting food from contamination and keeping it fresher for longer, while helping to reduce unnecessary food waste. It also protects a variety of high value consumer products, from pharmaceuticals to toys, razors and batteries. In healthcare, vinyl is used in many critical medical items, such as intravenous fluid bags and oxygen hoses. Although a small volume polymer packaging material, it has specific, necessary uses with a relatively low environmental footprint compared to alternatives.

Without doubt, vinyl has revolutionised the way we live our modern lives, helping to deliver safer healthcare, protecting our food and delivering drinking water. Given the high profile of plastics in the media, attention must focus on how we treat this recyclable material at end of life and recover it for beneficial reuse, including energy.

Post-consumer rigid PVC packaging is collected by most local councils around Australia. With existing infra-red sorting technologies, it can be sorted into a defined stream, reprocessed and used as recyclate for use in new products manufactured in Australia. However, at just over 5% of all plastic packaging materials (industrial and consumer) used in Australia, vinyl packaging is only a small proportion of total household packaging waste and is often considered uneconomically viable to sort and recycle.

The 2017-18 recycling rate of PVC packaging waste in Australia is reported to be 7.2% - which is low when compared to the overall average rate of 20.6% for all plastic packaging. (Source - 2017-18 Australian Plastics Recycling Survey published by Envisage Works, 30 January 2019). Nevertheless, clean, separated vinyl waste has value and collection has been actively encouraged by industry.

Clean, separated vinyl waste is relatively easy to recycle, requiring less energy for reprocessing than all other polymers. Using recycled vinyl in new products replaces virgin material and reduces carbon emissions associated with manufacturing virgin vinyl by about 80 to 85%, significantly lowering the carbon footprint of new vinyl products.

While technology exists to identify and sort PVC, few Materials Recovery Facilities (MRFs) are currently operating these systems because of ‘low volumes’. Yet substitution of a small handful of PVC packaging items would almost certainly lead to higher environmental impacts and higher waste volumes in terms of food waste, product damage or alternative non-recyclable composite packaging materials. It will also not remove PVC entirely from the waste stream, so an effective solution to remove PVC ‘contamination’ would be required regardless.

In my view, we need to consider whether the system of use is ‘open’ or ‘closed’ and how these waste plastics can be collected and recovered effectively in both systems for processing into new products, giving it a value as a raw material.

Examples of a ‘closed’ approach might be a major event, an airline or a hospital, where all the plastic waste can feasibly be collected, sorted, segregated and ultimately recycled as single, clean polymer waste streams. An excellent example of PVC packaging being collected and recycled is that of IV bags in healthcare. Schemes in Australia (our PVC Recycling in Hospitals Program), South Africa, Thailand and the UK successfully demonstrate that this material can be separated at waste source, collected and recycled into useful new products.

Conversely, in an ‘open’ system, such as take-away restaurants, all ‘control’ of these waste plastics is lost once single-use plastic walks out the door.

As a material that meets so many of our modern-day needs effectively, we should give careful consideration to how we treat and reuse PVC at end-of-life.

Solution options should cover:

- Separating PVC at source in ‘closed’ consumption systems to achieve a clean waste stream, such as the hospital PVC recycling program. This requires committed collaboration by brand owners, users and the PVC packaging industry to explore the feasibility of establishing collection and recycling schemes, and ultimately, end markets

- Using existing or new techniques and technologies to better separate PVC from co-mingled waste streams at a greater number of Secondary Sorting Facilities around the country, after the removal of higher volume PET and HDPE

- Researching, assessing and supporting the commercialisation and adoption of new technologies – such as chemical separation – to improve production of clean, single material streams for reprocessing

- Developing Waste to Energy projects for co-mingled residues

Demand is growing from manufacturers to increase the use of vinyl recyclate and signatory companies of our long-established PVC Stewardship Program are publicly committed to using recyclate in new products where standards permit.

Through greater collaboration between industry, manufacturers and the wider waste and recycling sector, the vinyl industry can be part of the solution and transform our plastic waste into a sustainable future resource.

More...

Partnerships aid progress in vinyl sustainability

Written by Sophi MacMillanGlobal vinyl industry partnerships are driving progress in the sustainability of the Australian PVC industry, resulting in the creation of successful initiatives such as best practice manufacturing, product stewardship and recycling.

Sophi MacMillan, Chief Executive of the Vinyl Council of Australia and a member of the Global Vinyl Council, believes that partnership is ‘absolutely integral to the work that we do as an association focused on sustainable development of the industry’.

During a panel discussion at the recent VinylPlus Sustainability Forum 2019 held in Prague, Czech Republic, Sophi emphasised the importance of partnerships for sharing knowledge, experience and strategies with experts from all the regions of the vinyl world.

“Attending the Global Vinyl Council meeting and the European Vinyl Sustainability Forum provides a great opportunity to build connections across the industry beyond Australia and our region. For the Australian vinyl industry, which is a small market, partnerships have been essential to us to move forward, to be able to tap into the knowledge of people, particularly in Europe and the US.

“It’s these connections that help us to develop our voluntary, industry PVC Stewardship Program and our initiatives around recycling, as well as sharing ideas and best practice.”

The Vinyl Sustainability Forum, organised by VinylPlus, the voluntary sustainable development commitment of the European PVC industry, attracted more than 170 participants from 32 countries to share further progress towards advancing the sustainability of the industry and its products.

Sophi continued: “Europe’s VinylPlus program is a leader in striving towards sustainable goals across the whole vinyl industry supply chain. Here at the Vinyl Council of Australia we follow in their footsteps with our own PVC Stewardship Program that has driven continual improvement in the vinyl industry for 17 years. We see stewardship as being a shared responsibility, so it is about working with, not just industry members, but also stakeholders - particularly government and NGOs - and trying to establish constructive partnerships.

“It’s about being aware of different epistemologies – different ways of knowing – which can help us to remove blinkers, to understand and characterise issues and develop paths to address them.”

Nowhere is this more important than in addressing the need for the industry to engage in the circular economy. Sophi highlighted their successful PVC Recycling in Hospitals Program, which now has 175 hospitals across Australia and New Zealand participating in the collection of PVC medical products for recycling back into new products, and through collaboration, is being implemented in other countries such as South Africa, the UK and Thailand.

In Australia, partnering with medical devices manufacturer Baxter Healthcare, PVC recyclers, medical waste collection companies, state governments and health authorities has been essential to developing and successfully delivering the program.

Sophi added: “Collaboration with the nurses and midwives’ union has also been very helpful in terms of finding pathways to engage nursing staff and to develop training on which medical products are recyclable under the program.”

A further example was given of the Council’s partnerships with academia such as Monash University and manufacturers in the development of product concepts for vinyl recyclate.

The Vinyl Council would like to see such wider collaboration form between stakeholders, particularly end-user brands, in the broader plastics packaging space.

“By working together, we have more knowledge, more ideas and are better equipped to find solutions to seemingly intractable problems.”

Ducting systems join Best Environmental Practice PVC Register

Written by Sophi MacMillanThe Vinyl Council of Australia has added a new category – PVC Duct Systems – to its Best Environmental Practice PVC Product Register in response to the growth in the use of low-profile PVC ductwork systems.

The EcoDuct 300 Series is the first product in this category to carry the Vinyl Council’s Best Environmental Practice (BEP) PVC trade mark. This mark is awarded to independently assessed, Best Practice PVC-compliant products that meet stringent life cycle criteria, developed by the Green Building Council of Australia.

Incorporating up to 50% recycled PVC, the newly accredited EcoDuct is a low impact, fire retardant duct system that is specifically designed for high-rise apartment applications where limited ceiling spaces are common. It is also 100% recyclable at end of life.

The Vinyl Council’s BEP PVC Register covers a wide range of BEP-accredited construction products. PVC Duct Systems joins existing categories covering flooring, resilient wall coverings, pipes & fittings, conduit/fittings, fencing, cable and permanent formwork.

Manufacturers of products holding BEP PVC accreditation have undertaken the vigorous, third-party assessment process required to verify their minimal environmental impact. The Vinyl Council then vets the certificates and records the products, suppliers and certificate validity on an online register.

The Council’s Chief Executive, Sophi MacMillan says: “PVC is a versatile material that offers a cost-effective, durable and low maintenance solution for a wide range of construction products.

“Best Environmental Practice PVC accreditation is an established quality mark for PVC, or vinyl products that helps specifiers to choose sustainable products manufactured to the most stringent environmental criteria.

“In addition to being recognised in Green Star’s Responsible Building Materials credit, Best Practice PVC is a valuable aid for specifiers and anyone procuring PVC products; and the online register makes it simple to identify those items made to the highest sustainable standards.”

You can find out more at /in-greenstar/best-practice-pvc-product-register

Life cycle thinking leads to new, engineered vinyl alternative to timber scaffold planks

Written by Sophi MacMillanPVC’s versatility and sustainability in construction applications is amply illustrated by TechBoard, an innovative product developed by Vinyl Council of Australia member Tech Plas Extrusions Pty Ltd.

A specialist in custom complex extrusions, New South Wales-based Tech Plas was one of the first signatories to the Council’s PVC Stewardship Program established 15 years ago. One of the Program’s commitments is to apply life cycle thinking to the development of new products.

Five years of intensive research and development has gone into TechBoard, a revolutionary new plank designed to last longer and provide much lower life-cycle costs than timber-based planks, with major environmental and economic benefits in the scaffolding and access industries.

As Andrew Swann, Tech Plas Business Development and Sales Manager, puts it: “We have optimised both profile geometry and material choice to produce a long-lasting, lightweight, recyclable, chemically-inert and customisable product that is an ideal timber alternative.”

Manufactured with a robust hexagonally-reinforced structure, TechBoards are designed to last so they will not swell, are impervious to weather and water, will not corrode and are non-contaminable. Because they won’t degrade over time, Andrew says, maintenance and storage issues and associated costs are significantly reduced.

The company says they are easier and safer to handle, offering weight savings of up to 40% per plank. Their weather-resistance makes maintenance and storage significantly easier by removing the costly requirements for undercover storage and drying.

Within the Australian and New Zealand scaffold industry the use of timber LVL (Laminated Veneer Lumber) boards is commonplace despite being utilised in environments to which they are not compatible, says Andrew. This leads to nearly 1 million m3 of damaged boards going to waste annually and significantly reduced longevity.

“This is a staggering amount of waste that led us to create our own industry-specific solution with sound environmental credentials.” continues Andrew, “However, introducing a new product for a previously-unexplored market meant we had to overcome some challenges.”

Gaining market entry and acceptance required close industry collaboration – not least in ensuring that TechBoard meets all relevant ANZ and international standards, including AS/NZS 1577:2013.

Industry partnerships, including end users, contractors and specifiers, were crucial in gaining acceptance, such as in the water and wastewater treatment sectors. “Once they’d used TechBoard, they loved it,” says Andrew. Further refinement work followed and Tech Plas developed a number of accessories for the internationally-patented 230mm x 40mm TechBoard. These include safety ramps to prevent trip hazards, plank joiners, end caps and conductive accessories to mitigate static build-up.

TechBoard has applications well beyond the scaffolding and access industry uses, such as retaining walls, noise barriers on freeways, boardwalks and pedestrian access – even planking on submarines.

Andrew added: “We’re proud of TechBoard’s lifecycle savings. Capable of lasting five years, being made from PVC means that it can be readily recycled at end-of-life and used to make new TechBoards.

“After five years of use, we aim to recover the used boards for recycling, thereby reducing environmental impact. Our intended recycling process leaves a clear carbon trail for sustainability.”

The recyclability of PVC packaging in Australia

Written by Super UserPVC (vinyl) packaging - designated by the Plastics Identification Code number 3 - is recyclable.

Vinyl has long been used on a global basis to meet specific functional food and beverage packaging needs. It offers users excellent clarity, unsurpassed physical properties including heat tolerance, controllable gas and moisture vapour transmission capabilities and exceptional sealing performance. Unlike many other materials, Vinyl can be formed into a myriad of complex and functional forms to suit many different food types.

Most vinyl (>85%) is used in long life products, particularly building products, such as potable water pipe, conduit, cabling, flooring and window profiles, all of which are also recyclable in Australia. Vinyl used in packaging represents approximately 5 percent of the material’s usage in Australia.

Vinyl packaging is commonly used for clear, handled bottles such as for cordials; clamshells to protect fresh fruit, vegetables, bakery and other fresh food items; and as very light gauge film for wrapping and protecting fresh meat, produce, dairy and deli products. Vinyl plays an important role in keeping fresh food fresh, and in turn benefits consumers by protecting the fresh food from early spoilage or other forms of undesirable food contamination.

Vinyl is also used as secure blister packaging for high value products such as pharmaceuticals, batteries, razors, toys, and an array of other consumer products. An important material for healthcare, Vinyl is used in many critical medical items, such as intravenous fluid bags and body fluid hoses, used in the delivery and management of blood and other fluids in operating theatres and similar critical care situations.

Post-consumer PVC packaging is collected by most local councils around Australia and by industry directly from the healthcare system. It can be sorted into a defined stream, can be reprocessed and used as recyclate for use in new products manufactured in Australia. However, at just over five percent, vinyl packaging is only a small proportion of all plastic packaging materials (industrial and consumer) used in Australia.

The 2017-18 recycling rate of PVC packaging waste in Australia is reported to be 7.2% - which is low when compared to the overall average rate of 20.6% for all plastic packaging. (Source - 2017-18 Australian Plastics Recycling Survey published by Envisage Works, 30 January 2019).

Clean, separated vinyl waste has value and collection is actively encouraged by industry.

Rigid vinyl packaging

Rigid vinyl packaging such as bottles and thermoformed packaging is recyclable when collected from kerbside and sorted from other polymers and packaging materials. Most councils around Australia have included these products in collections for many years.

Post-consumer vinyl bottles are separated out where manual sorting systems operate at Materials Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and sent to recyclers. The Vinyl Cycle bottle recycling program that operated for many years (until 2012) demonstrated that a recycling rate of over 50% was achievable when vinyl bottles were manually sorted for recycling, however very few MRFs operate such systems today.

Optical sorting technologies exist based on Near InfraRed cameras that can identify polymer types, including vinyl, and colours (except black). These achieve high purity streams, generally 93-96% for most polymers. In Australia, however, use of such technologies has largely been limited to identifying the dominant two packaging polymers only – PET and HDPE – despite local demand for recovered vinyl for remanufacturing within Australia.

Post-industrial rigid vinyl packaging materials, such as thermoforming web scrap, is sought after by recyclers for use in other products.

Flexible vinyl packaging

A successful program currently operates across Australia’s healthcare sector. The ‘PVC Recycling in Hospitals’ scheme operates in over 170 healthcare facilities in Australia and New Zealand and collects approximately 15-20 tonnes a month of vinyl intravenous bags, tubing and oxygen masks. This material is reprocessed locally into new, long-life products. The success of the program is, in part, due to the separation at source of the vinyl products, reducing contamination from other polymers and materials.

Unfortunately, there is little collection and recycling of post-consumer films and food wrap, regardless of polymer type. This is due to a number of reasons - high contamination from dirt, food waste and other non-plastic materials and contaminants; the wide range of polymers and other materials used to manufacture films, such as mono layer, multilayer and mixed polymer films; and the risk of films generally entangling and damaging traditional processing equipment at the MRF.

Nevertheless, the vinyl film industry in Australia has taken appropriate actions to reduce raw material use through down-gauging films and continually seeking ways to reduce the life cycle footprint of these products by way of material selection.

Benefits of sorting and recycling vinyl packaging

Clean, separated vinyl waste is relatively easy to recycle as vinyl is a thermoplastic. Vinyl’s melting point is relatively low which means less energy is required for reprocessing vinyl than that of other polymers, but this has been the reason it is considered a ‘contaminant’ in other polymer streams as it burns at higher temperatures.

Industry does not see vinyl as a contaminant; we see it as a resource. There is very good reason therefore to implement technologies and systems to separate vinyl early in the kerbside waste sorting process.

Using recycled vinyl in new products replaces the use of virgin vinyl compound and reduces the carbon emissions associated with manufacturing virgin vinyl by about 80-85 percent. This significantly lowers the carbon footprint of new vinyl products.

Local manufacturers of vinyl products have indicated that they have an appetite to increase the use of vinyl recyclate if reliable, continuous sources of recyclate are made available. Signatory companies to the long-established PVC Stewardship Program are publicly committed to use recyclate in the products they supply to the market unless product standards prohibit it.

The Council therefore welcomes emerging initiatives by MRFs to separate rigid vinyl packaging and some other flexibles for local reprocessing and reuse in Australia.